When a Congolese student ran against the white Greek establishment for University of Alabama’s student government presidency, the campus was forced to confront its history of racial strife.

Confident, articulate and an honors student at the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa, Fabien Zinga seems like an ideal candidate for student government president. But if the recent flurry of racist messages is any indication, not everyone thinks this black pre-med student belongs on the ballot.

In the lobby of Burke Hall residence, Zinga plays a message he received during the height of his campaign efforts. A male voice whispers, “Fabien, nigger we’re going to hang you from a tree.”

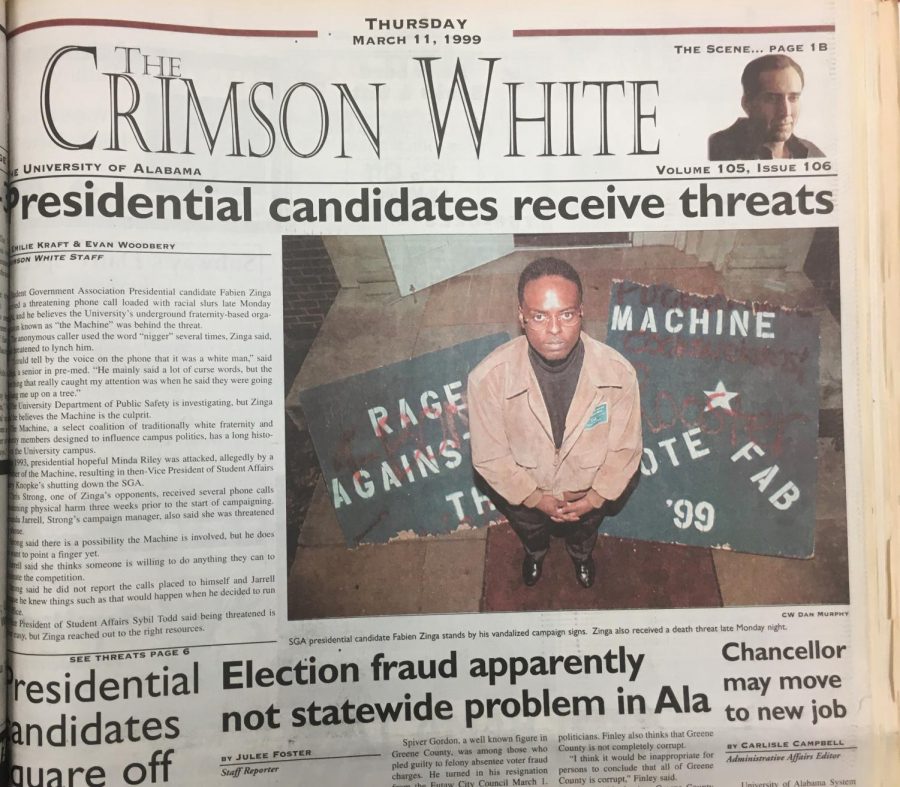

The college senior recently reported this and other harassment phone calls to campus police. In addition, 12 of the 14 wooden campaign signs the Congo native posted around campus were defaced with racial and other epithets.

“I must tell you that when I first received these calls I was very, very scared,” says Zinga.

Lt. Beth Turner of the university’s Department of Public Safety says the matter is under investigation, but will not comment any further. Harassing communication is a misdemeanor, with possible punishment ranging from one day to one year in prison, she says.

University officials say they may also involve the FBI. Although no one is arguing that such racial slurs are everyday occurrences at the University of Alabama, Zinga’s case has stirred debate about racism on campus and a secret society of elite white students called “the Machine.”

Zinga thinks the Machine might be behind the threats. According to university students and faculty, the group is composed of members from the oldest white fraternities and sororities and has historically dominated campus politics. Like Yale’s Skull and Bones, the Machine has an extensive history on campus but it is even more elusive. Because no one will admit to being a member of the Machine and those fraternity and sorority members associated with it are the ones who often claim it’s merely a myth, some have doubted the group’s existence. But most conversations about student government or Greek life inevitably yield several references to the Machine and its influence.

Some students have not only doubted Machine involvement but the truth of Zinga’s harassment claims. But others say the harassment of students who oppose Machine-endorsed candidates is nothing unusual. In 1993 the university shut down the Student Government Association for three years after student Minda Riley — a white sorority member but not the Machine-endorsed candidate — was allegedly attacked by a Machine member. And in addition to Zinga, another student government candidate in this year’s race claims to have received phone calls threatening physical harm.

Why would anyone care so deeply about a student government election that a majority of students don’t even bother to vote in?

“Student government becomes the springboard for state politics,” explains associate English professor Diane Roberts, who has written about the UA Greek system. “It’s not just a little line on your CV. This is the elite university of the state.” As evidence, she notes that Alabama Gov. Don Siegelman belonged to Delta Kappa Epsilon, reputedly a Machine fraternity, and was student body president.

Cedrick Rembert, an engineering student and president of UA’s Pan-Greek Council, the governing body for black fraternities and sororities, believes that Zinga — whose campaign slogan was “Rage against the Machine” — may have been targeted because of his vocal stance against the coalition. Opposing the Machine is “a very strong issue,” he says. “That’s the underlying message of anyone who runs in the election, but [Zinga] is the only one that has directly said it.”

While the Machine may be part of the controversy, the racist nature of the alleged harassment suggests that Zinga’s skin color is also an issue.

The Congolese student isn’t the first to accuse the university’s white Greek system of racism. In 1986, someone put a burning cross on the lawn of Alpha Kappa Alpha when it was the first black sorority to move into Sorority Row. In the early 1990s, fraternity members booed a black homecoming queen while sorority women made headlines in the New York Times when they appeared in blackface and Afro wigs to a “Who Rides the Bus?” social.

“We have 16,000 students and occasionally one of them decides to do something stupid,” says Bob Sigler, professor of criminal justice and chair of the student and campus life committee. He calls such incidents “rare” and

says the students involved in the cross-burning incident were suspended.

But English professor Pat Hermann is less willing to see such incidents as anomalous. He criticizes the university for not making public the results of an investigation that looked into racist charges made by a house mother at Alpha Alpha Omicron Pi sorority. Gertrud Breier claimed she was dismissed for allowing black house workers to eat in the kitchen, rather than the usual maintenance room. Hermann has also denounced the university’s white Greek system for never having admitted a black student, labeling it “100 percent apartheid.” University of Alabama is one of only a handful of schools in the Southeastern Conference that has never had a black member in its white Greek system, although some black fraternities have had white members in the past and some white fraternities have admitted Asian-American members.

With the formation of committees such as the Rush Task Force and the Greek Diversity Task Force, University of Alabama has recently stepped up its efforts to create more diversity within its white Greek system. Ashley Gnemi, past president of Pi Beta Phi sorority, says efforts of the Rush Task Force will help sororities that are interested in promoting diversity but “just don’t know how to do it.”

But Hermann says these committees only give “the illusion of progress.” As early as 1985, the faculty senate passed a resolution asking for Greek integration. And in 1991 Hermann chaired the Greek Accreditation Committee, which targeted 1996 as the year for integration.

(This prompted the 1991 New York Times headline “University of Alabama: Integration Is at Hand for the Fraternity System.”) But in 1999 no blacks have become members of the white Greeks. Last fall two black female students rushed the white sororities but received no bids. Now the university is “reinventing the wheel,” says Hermann.

“If the university were serious about [integration] it would take about five minutes to solve this problem,” says Hermann, who suggests that instead of such task forces, the university should punish racist Greeks by shutting them down. But neither black nor white Greek members want the university telling them what to do. Jamese Young, president of the black sorority Delta Sigma Theta, says that forcing integration would “degrade the quality of membership” for both white and black Greeks.

Some UA administrators were hoping that Rush Task Force members — which included both black and white Greek students — would agree to delay white Greek rush until closer to the time when black Greeks hold rush, during the spring. (This measure was recently enforced by the University of Mississippi). “In a uniform or all-encompassing rush system, black and white students would at least meet their counterparts in rush,” says Hank Lazer, assistant vice president for undergraduate programs. But the Rush Task Force rejected such changes.

“If the university were serious about [integration] it would take about five minutes to solve this problem,” says Hermann, who suggests that instead of such task forces, the university should punish racist Greeks by shutting them down. But neither black nor white Greek members want the university telling them what to do. Jamese Young, president of the black sorority Delta Sigma Theta, says that forcing integration would “degrade the quality of membership” for both white and black Greeks.

Some UA administrators were hoping that Rush Task Force members — which included both black and white Greek students — would agree to delay white Greek rush until closer to the time when black Greeks hold rush, during the spring. (This measure was recently enforced by the University of Mississippi). “In a uniform or all-encompassing rush system, black and white students would at least meet their counterparts in rush,” says Hank Lazer, assistant vice president for undergraduate programs. But the Rush Task Force rejected such changes.

Pan-Greek’s Rembert also believes that the first white Greek organization that admits a black member would be outcast. “That’s a big first step to take and I don’t think anyone is ready to take that step.” He might be

right, considering that some students mistrust the university’s motives for trying to promote Greek diversity. As Kappa Alpha’s Willis puts it: “A lot of people here want to be known as the person who integrated the Alabama Greek system.”

Although Greek integration could undermine the white power structure, there are some who believe the real threat will be to the taboo of interracial dating. Joining Delta Delta Delta over Kappa Kappa Gamma not only may determine a student’s future job prospects but also her marriage partner. White Greeks hold “swaps” — social events in which fraternity and sorority members pair up for social events. Greeks become “channels for business and marital relations,” says Lazer.

Although assistant vice president Lazer doubts that the University of Alabama’s Greek integration efforts will have much impact, he believes the university has made progress in other areas of race relations since the days of segregation, citing an increase of African-American student enrollment in last year’s freshman class, up to 16 percent. Rose Gladney, associate professor of American studies, says that during the 25 years she has been teaching at the university, she has seen a “stronger commitment to hiring and retention of minority faculty.” She adds that the appointment of the Diversity Oversight Committee shows institutional commitment to diversity awareness year-round and “not just during African-American history month.”

But perhaps any hope that the university will make real racial progress in the new millennium rests on the shoulders of the student body itself.

Student apathy has fueled the Machine’s ability to control campus politics and drowned out many other student voices — from African Americans to students who eschew the Greek system all together. Dawne Shand, a 1992 UA graduate, recalls that during her time at the university, “independents” — as non-Greeks are called — were neglected by the university. “The administration always catered to the more organized student organization,” she says. “You would never hear them talk about issues that were not important to non-Greeks.” As a result, the white Greeks — though only about 14 percent of the student body — have represented the largest organized group on campus.

Last year, no one ran against reputed Machine-endorsed candidate Bill Hankins. But this year, with a total of four student government presidential candidates, more voices are challenging the Machine-endorsed candidate. And students say that this year has seen the most SGA presidential candidates since the administration reopened

student government in 1996.

For “too long, SGA represented a very small percentage of this campus,” says Zinga.

Jason Rogers, a sophomore and studio art major who made Zinga’s campaign signs, says he wasn’t even going to vote until he heard that such a small minority governs campus politics. He then decided to get involved in Zinga’s campaign because his platform involved opening up student government to a broader array of students. Rogers also hopes that recent harassment charges will “get students to open up their eyes a bit more.” That might already be the case: Recent campus events have centered around getting more students to become politically active.

Many students have also come to Zinga’s defense by organizing rallies — without Zinga’s prodding — to combat racism and by sending him a letter of support with about 80 signatures. “If it wasn’t for their support I think I would have dropped out [of the race],” says Zinga. He insists that only a small percentage of the university community is racist and remains certain the harassers will be apprehended.

Long before the threatening phone calls and the subsequent outpouring of support, Zinga felt a debt of gratitude for his university. A few years ago, when a civil war broke out in the Republic of Congo, he couldn’t contact his parents. “I was drinking water and eating bread. I had no money,” he says. The university came to his aid with scholarships and emotional support. His decision to run for president was sparked by a desire to “thank the University of Alabama for everything they have done for me.”

But according to the election results posted Thursday, the voices opposing the Machine were not loud enough to allow Zinga to repay his community. Zinga lost in this year’s campaign to reputed Machine-endorsed candidate Matt Taylor, who captured 42 percent of the student vote. Although only 36 percent of campus undergrads voted in the election, it was a record turnout in the university’s student government history.